Office applications like OpenOffice.org can bring out the worst in people. The same people who wouldn’t dream of driving a car without a few lessons will start pounding away in a word processor as though it were a typewriter, ignoring basic features like styles and templates. In the end, they may produce the documents they want, but only with far more effort than is necessary. They might as well be pushing a car instead of turning the ignition key.

Nothing stops you if you really want to format manually, any more than anything prevents you from using the soles of your shoes to slow down a car instead of the brake. OpenOffice.org does nothing to stop you from indenting each new paragraph in Writer or setting each number format in a Calc cell on its own. For small, unusual documents, manual formatting may even be quicker.

By Bruce Byfield

But to insist, like some people I’ve heard, that any alternative is too hard to learn, or an attempt to restrict users’ freedom simply makes life difficult for yourself. Using styles takes a different perspective and may require more initial planning than manual formatting, but it makes reformatting much easier. It also makes tools like outline numbering or generating tables of contents far simpler to use.

That is true of any office application, but it is doubly so in OpenOffice.org, which is far more organized around styles than most of its counterparts. If you really want to get the most from OpenOffice.org, you need to start using styles, and know what they can do in each OpenOffice.org program.

STYLE BASICS

A style is a collection of formatting instructions that you set once and then apply as needed throughout a document. For instance, in Writer, you might create a title style for italicizing the names of all the books mentioned in your document. If you decided to put the document online, you could change all the italicized book titles to a bold font for easier reading by changing the style, instead of going through the document and changing each title individually and maybe missing one or two instances.

Similarly, you could create a first, right, and left page in Writer, and have the correct one appear automatically. In Calc, you could apply complex formatting to a cell with a single mouse click, or duplicate an object endlessly in Draw.

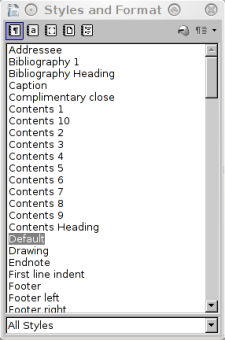

You can see a list of styles in any OpenOffice.org program by selecting Format -> Styles and Formatting, or by pressing the F11 key. Either way, you open the Styles and Format floating window that you’ll want to keep open as you design your document and format it. If you want, you can move it outside the editing window so it doesn’t cover any of the document.

At first, you may want to confine yourself to the styles that OpenOffice.org has set up. However, when you start adding your own styles, you will probably want to follow OpenOffice.org’s example and name your styles for their function in the document, rather than “red default text” or “small text.” Following this habit will mean that you don’t need to rename styles as their formatting changes.

At the top left of the floating window are icons for displaying the different types of styles available in the program. Writer is especially rich in styles, with no less than five types, but all the OpenOffice.org programs have at least a couple of types

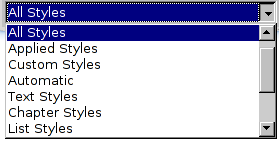

By default, OpenOffice.org shows all the available styles for a type — and, especially in Writer, that can be an overwhelming lot of them. Fortunately, you can make your life saner by changing the view at the bottom of the Styles and Format floating window. You can change the view to a particular category of related styles, or choose Custom Styles to see only the ones that you have added, or Applied Styles to see only the ones that you are using in the document.

If you select the Hierarchical view, you will see that some styles depend on others. For instance, the Heading 1, 2, and 3 styles, as well as the Title and Subtitle styles, are dependent upon the Heading style. That means that, if you suddenly decide to change the font used for headings in your document, you change the font in the Heading style, and change the font in all these other styles at the same time.

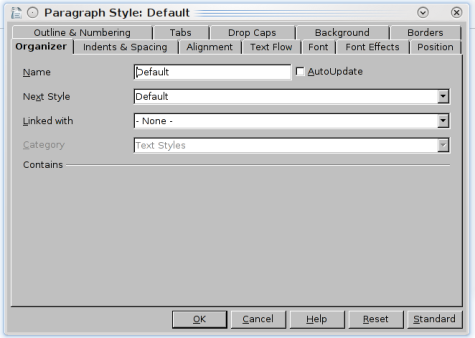

To modify a style, or to create a new style based on an existing one, right-click on a style in the floating window and make a selection from the context menu. If you want to create a style not based on any other style in particular, click the Default style, which is at the top of the hierarchy of styles.

In the top right of the floating window are two other tools. One is Fill Format Mode, which allows you to select a style, then apply it like a paint brush to your document. The other is New Style from Selection, which allows you to select an already-formatted part of your document as the basis for a new style. You don’t need to use either of these tools, but they can be handy if they fit your style of working.

WRITER STYLES

OpenOffice.org’s word processor has five different types of styles: paragraphs, characters, pages, frames, and lists. The dialog window for each type of style includes an organizer style, where you can edit the name of a style, the style it is based on (if only Default), and, in some cases, the next style that is used. Setting the Next Style can be a useful way to automate, so that a Heading 1 style is followed by a Textbody style, or a Right Page style is followed by a Left Page with no intervention on your part.

The most basic type of Writer style is paragraph styles, which apply to all the text between two places where you press the Enter key. When you edit a paragraph style, you can edit the typeface and its weight, the line alignment, how it is hyphenated, and other basic features. If you want to be more elaborate, you can give the paragraph a border or a colored background as well, or create drop capitals for its start or assign a list style.

Paragraph styles include several features on the Indent and Spacing tab that mean you can keep your hands on the keyboard and not have to worry about adding formatting. By setting the spacing above and below the paragraph, you can add spacing between paragraphs automatically. Similarly, if you set a First Line indent then make it automatic, you can almost entirely ignore the Tab tab in the style dialog window and the Tab key on your keyboard.

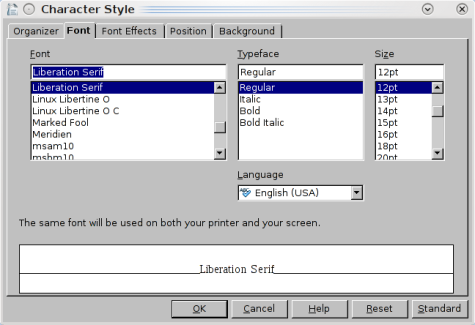

After paragraph styles, character styles are the most commonly used. As their name suggests, character styles are used to edit blocks of text that are smaller than paragraphs, such as the titles of books or the numbers for foot notes in the text. Since they replace the formatting of the paragraphs in which they are used, character styles contain many of the same basic settings as paragraph styles, especially the ones to do with fonts and font effects. They contain nothing flashy, and in many ways are the workhorses of Writer’s styles.

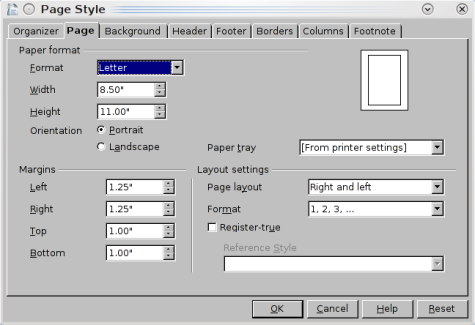

By contrast, page styles are often overlooked, but are worth a closer look because they give Writer many of its desktop publishing capabilities. If you want multiple headers and footers, you need to design separate page styles for each design. Page styles are also the easiest way to automate page numbering, or set the number of columns used. If you are writing academic papers, page styles also allow you to fine-tune the look of footnotes.

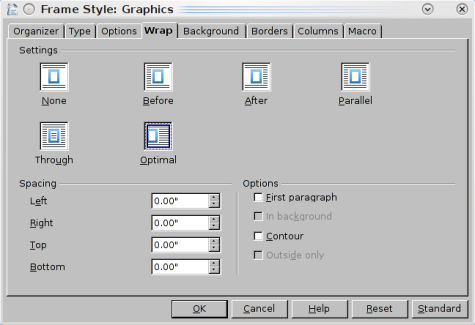

Frame styles are another feature largely used in desktop publishing. You can use frame styles to format the position, look, and size of objects like pictures that you add to a document. Many of the most important features in frame styles are on the Wrap tab, where you can set how text is positioned around the frame, and the distance that separates the text from the frame.

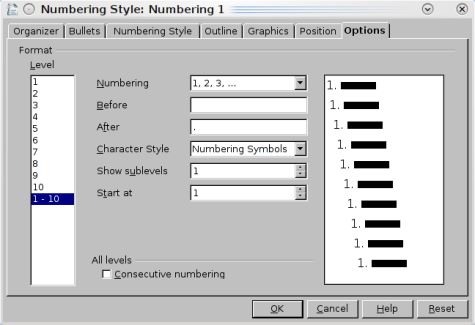

List styles are really a sub-category of paragraph styles, but are in a separate category because they contain a lot of small options. You can either select a numbering or bullet style from the default options, or create your own using the Position and Option tabs, specifying such details as the spacing between a number or a bullet and the text that comes after, or the characters that come first; for example, you could set up a list style so that each number was preceded by the word “Step,” was followed by five spaces before the text begins, and was formatted in the Default character style. When you are finished, you can then assign a style to a paragraph style, using the same list style in different paragraph styles to save yourself the effort of defining it twice. The default list styles, you’ll find, are divided by names: Numbering styles are for numbered lists, and List styles for bulleted lists.

STYLES IN CALC

Spreadsheets do not lend themselves to styles as well as text documents, but Calc uses two styles to make your life easier: Cell and page styles.

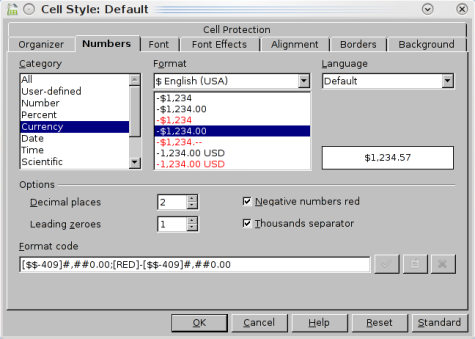

Cell styles are used for storing formatting for individual spreadsheet styles. They include general choices such as the font used, as well as more spreadsheet-oriented choices, such as the number format, which determines how a cell treats any numbers entered into it.

If you prefer that everything in a cell is visible at all times, you might want to set features on the Alignment tab of the Default tab. By selecting Wrap text automatically and Hyphenation option, you can ensure that cell contents is always readable, even when you do not have the cell selected. Alternatively, you can shrink the cell contents so that it fits the available space.

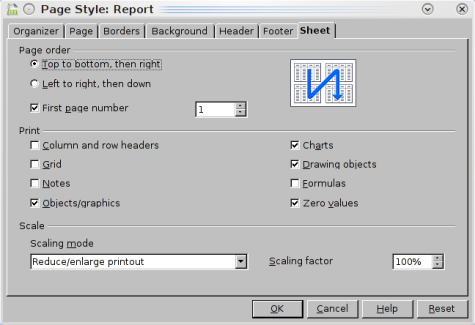

You will probably want to use cell styles regularly, but page styles are likely to interest you only if you plan on printing a spreadsheet — a task that is often a difficult process of time and error. The problem is not so much the choice of the font, the margin or the background color (all of which you can set in a page style) as how to translate the unlimited size of a spreadsheet on to the confines of a page. For this reason, the most important tab in the page style dialog is the Sheet tab, where you can set what is printed, and exactly how columns and rows are transferred to the printed page. Page styles will not always remove all of the trial and error, but they can make the process of printing much easier.

IMPRESS AND DRAW STYLES

OpenOffice.org’s presentation and graphics program use much of the same code. Unsurprisingly, then, their Style and Format floating windows show the same styles, graphic text and presentation styles, even though presentation styles are grayed out in Draw.

Presentation styles are Impress’s version of Writer’s paragraph and list styles. You can use them to adjust the titles and bullet points that you add to a presentation. They include many of the same features as paragraph styles, laid out in the same tabs, such as Fonts, Font Effects, and Indents and Spacing. Other tabs, such as Alignment, are simplified versions of their paragraph style equivalents, because Impress is less flexible about arranging text than Writer. You can also set Tabs if you like, although creating a table is probably a better option for complex positioning of text.

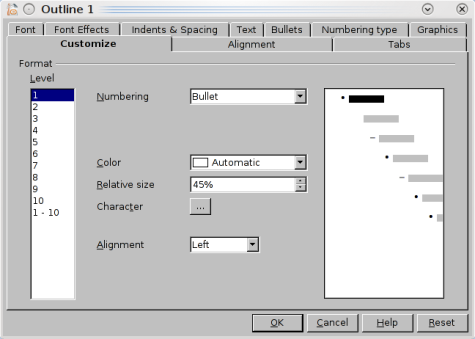

Other choices for presentation styles resemble those for list styles. You can choose a numbering style from the Numbering type tab, or a graphical bullet from the Graphical tab. Or, if you prefer, you can use the Customize tab to set all the details of your lists yourself.

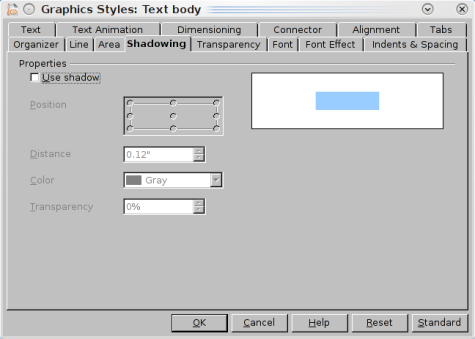

In contrast to presentation styles, graphic styles adjust the features of objects created in Draw or with the Drawing tool bar in Impress. These objects include simple geometric shapes as well as stars, flow chart symbols, and — rather confusingly, text that is treated as a graphic rather than ordinary text. With graphic styles, you can set such features as the line and fill for objects, or quickly give them a shadow or make them partly transparent. If text is involved with the object, you can also add much as the same formatting as you can with paragraph or presentation styles. Graphic styles are especially useful when you are creating many objects of the same type, such as the rectangles around names and titles in an organizational chart.

STARTING TO USE STYLES

This is only a quick introduction to the different types of styles in OpenOffice.org and how you can use them. A detailed description would require considerable space, and possibly create anxiety option. In general, you should start using styles lightly, at first using only those features that make immediate sense to you, and branching out into the more advanced settings gradually. Most of OpenOffice.org’s default style settings are reasonable ones for most purposes, so you can usually trust them until you are ready to control more of the details yourself.

Even so, you may find the initial job of creating styles takes some time and requires you to do some planning before you plunge into writing. You may need some time to get used to these changes, but you should find that, by separating the design process from the actual writing, using styles allows you to focus more on content when you do start to write.

Still, why repeat the process of design unless you absolutely have to? Create a Default template that contains most of your favorite settings, then add additional ones as you remember other types of documents that you use regularly. You might, for example, add a template for essays if you are a student, or for memos if you work in an office. By saving all your style-oriented documents as templates, you will save even more time, and remove much of the repetition from your work.

That, really, is the whole point. By helping you to get organized and think about what you are doing, styles can save you hours of what is essentially drudgery and leave you free to focus on what you are saying — and not on how it looks.

By Bruce Byfield

I’ve never used styles in any office suite, and generally I find they get in the way of formatting how I want a document formatted. However, while I may now have some interest in what they can do, how about showing us some examples? How about that ‘easier to reformat’ part, why not show what three styles can do to one document to show how they’re different?

@lefty:

Go to a website that has multiple styles and see what a simple stylesheet can do with the same text.

I would direct you to groklaw.net, but you have to register before changing the style of the website.

I can do the “easy to reformat” part, having had to do it more than once. Let’s say your default paragraph style has the first line indented, and no “spaces” (more precisely, new lines) between paragraphs. Font is 10-pt Arial. You write out a report, show it to your boss, who says 10-pt Arial is bad for the panel who’ll review your report, and asks you to change it to 12-pt Times New Roman. Also, the panel doesn’t want paragraphs with indented first lines, and would prefer a space between paragraphs to indicate a new paragraph. Also, they can’t stand paragraph justification and would prefer simple left justification. Instead of selecting (i.e., highlighting) the entire document and changing the paragraph style from there, bring up the Styles, select the default style, then do your changes there. Every paragraph formatted with the default style changes accordingly.

One reason you shouldn’t do the select entire document thingy is that you may have a coupl’a paragraphs — e.g., quotations from external documents — that have their own formatting, which will obviously change if you go that route. Change the default style from the style sheet, and those paragraphs that have their own formatting will keep their own formatting.

At the risk of blowing my own horn, I should mention that I wrote an article in Free Software Magazine that dealt with, among others, styles: http://www.freesoftwaremagazine.com/articles/the_lazy_user_s_guide_to_openoffice_org_writer

As to the article itself — I’ve had to use the “leading” office suite, and found that the Styles in the presentation and spreadsheet modules were hard to find, if present at all. Just thought I’d mention that, to let people know the OOo beats the “market leader” in at least that respect 🙂

Nice. But why in the world are there styles for everything but tables?

Pingback: Discovering OpenOffice » Blog Archive » Stylin’ in OpenOffice [Formatting for Calc and Writer]

Pingback: GoblinX Project » GoblinX Newsletter, Issue 238 (02/21/2010)

office suites are good only for creating small documents(not more than 10-12 pages) i have learnt that even for these tasks they are an overkill in terms of features and resource usage. for long/large documents, i have moved away from these and happily use a simple text editor to write my content, then use *TeX to mark it up these days … cs

Why no table styles? That’s a question I’ve been asking for nine years.

Writer does have the ability to save table patterns, but this falls far short of table styles.

“office suites are good only for creating small documents(not more than 10-12 pages) i have learnt that even for these tasks they are an overkill in terms of features and resource usage. for long/large documents, i have moved away from these and happily use a simple text editor to write my content, then use *TeX to mark it up these days”

Thank you for the obligatory TeX comment. No article on an office suite is complete without one.

Not that there’s anything wrong with TeX. But, unfortunately, the majority of people don’t know TeX, and aren’t about to use it.

Also, I’ve used OpenOffice.org for documents of over 700 pages, and had no trouble whatsoever with them.

I should also point out that, if had used OOo with a template in which the styles were set up, you could have done much of your formatting automatically as you worked, and reduced your working time by almost half.

Pingback: Links 26/2/2010: OpenSolaris Support Model to Change | Boycott Novell

As a long-time Adobe FrameMaker user and template designer for technical documentation 2 m wide, I feel the styles of OpenOffice are much like the styles inside FrameMaker (except indeed the table styles).

OpenOffice.org could very well be the replacement for FrameMaker for ultra-long and strictly consistent product documentation. I’ll give it a try with one of our service manuals.

Hello this is inderjeet from india, i am working on project which include to create functionality that let me change style sheet of .odt file to presentation ..

Can you help mee if soo plzz replyy..